Climate change, warming temperatures and an increase in nutrient density in the world's oceans are causing a steady loss of oxygen in the marine environment and posing a serious threat to biodiversity.

It's estimated that oceans have lost about two per cent of dissolved oxygen since the 1950s and are expected to lose up to four per cent by 2100. The loss rate can be more intense in some locations, such as coastal regions, and can lead to shifts in species distribution, reductions in fish stocks and biodiversity, and changes to nutrient cycling which drives increased greenhouse gas emissions or unusual algal blooms.

A growing region in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence Estuary is currently under threat from decreased oxygen in subsurface waters, due in part to a climate-related reduction in the supply of oxygen-rich waters to the gulf through the Cabot Strait between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.

Now in a new , scientists are suggesting one way to stem the loss would be to actually pump oxygen back into the ocean using a by-product of green hydrogen production.

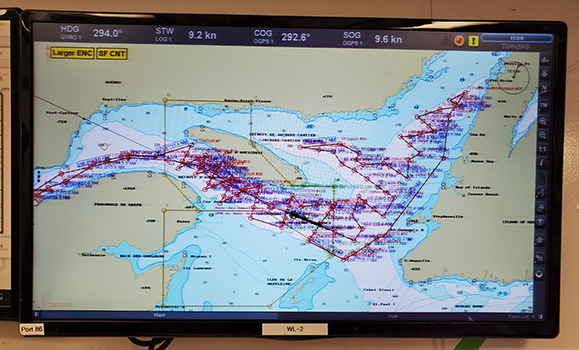

Research data displayed on a map of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Research data displayed on a map of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

A team of researchers at Dalhousie University has shown that the proposed green hydrogen industry could, regionally, produce more than enough oxygen to match what is currently being lost from the Gulf of St. Lawrence every year.

Oxygen generated in the production of hydrogen would typically be released into the atmosphere, but could potentially be diverted into the ocean to re-oxygenate the marine environment.

Dr. Doug Wallace, an ocean chemist and professor in Dalhousie's Department of Oceanography, led the research initiative with colleagues from Dalhousie, GEOMAR in Kiel, Germany, and McGill University. They added an inert, non-toxic tracer to deep water in the gulf about 130 kilometres from the location of proposed hydrogen plants, and demonstrated that injected oxygen would travel to threatened regions in 1.5 to four years.

The study was supported by the and .

Contact

Media interested in more information on this discovery, contact Alison Auld