Eighteen months ago, Mike Young, a senior instructor in Dalhousie’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, bought a drone to start collecting images and videos of the unique field sites he visits in his courses. Young, who teaches second- and fourth-year field geology courses in the Faculty of Science, wanted some ways to provide his students a more immersive introduction to field trips prior to actually going to the field.

“Some students are more comfortable in the woods than others,” says Young. “For some, it can be quite intimidating to arrive at a field location where you must contend with wind, cold, rain, animals, no bathrooms and the sheer scale of the outdoors. I wanted my students to feel as comfortable and prepared as possible before getting into the field,”

When the peak of COVID-19 hit, he knew his idea of virtual field trips would be accelerated and would have to become an essential component of the fall semester.

“We know that field trips are a major part of the Bachelor of Science program, and since students cannot go into the field together this fall, we decided to bring the field to the students.”

Using modern visualization techniques, he and his team are building over 20 virtual field trips, complete with 3D models, video footage, photogrammetry and other high-resolution visualizations. The team has had to move quickly with the gear and budget they had available but did not want to compromise on quality of both the visuals and content.

“I wanted my colleagues to be able to teach to their strengths using local field sites and I wanted students to be able to interact with high quality visualizations without the frustrations of low-resolution images or poor quality audio,” says Young.

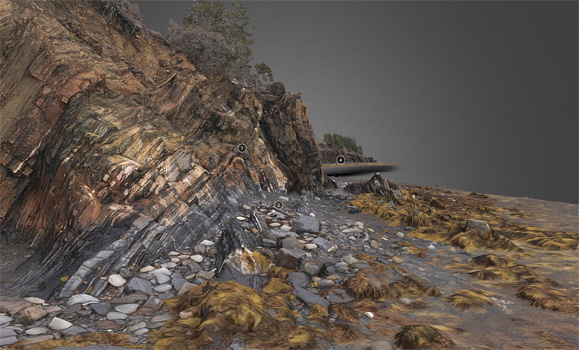

“We’re currently building 3D models, some of which include kilometer-long stretches of coastal cliff sections, tidal flats and rocky outcrops in hard to reach places.”

Digital depth

The 3D models are generated by a process called Structure-from-Motion. It’s a specialized type of photogrammetry where three-dimensional structures can be estimated from overlapping two-dimensional images — a digital technique similar to how we see depth with our two eyes. Students will get an even better sense of the three-dimensional space than just a series of photographs.

“In the case of digital imaging, I fly the drone around a cliff and beach in a regular and overlapping grid pattern – vertically against the cliff and horizontally over the beach – and specialized software reconstructs the three-dimensional features.”

A 3D-rendered, annotated image of The Ovens shoreline in Nova Scotia.

His team has also created ultra-high resolution gigapixel panoramas that will allow students to zoom from the 100-meter outcrop scale to the 1-centimeter mineral scale. The videos they’ve created also have course instructors at their field sites explaining various features, and their significance to larger concepts or problems. These different media will be compiled together in an online geospatial application easily accessed by web-browsers. Students won’t have to install software or download data.

Recently, he also flew a pre-programmed survey along an 800-metre stretch of the coastal section at Joggins Fossil Cliffs. The ‘zoomable’ panoramas are created using a tripod-mounted device called Gigapan. The technology comes from NASA’s Mars Rover program where the device is programmed to take a series of overlapping photos from a single position and then they are automatically stitched together. The Gigapan moves the camera and triggers the shutter until the scene is captured. Some of the panoramas Young has produced include over 300 photos taken with a 300 mm lens. This is why you can zoom in so far and not lose resolution.

A new way of looking at Nova Scotia

Creating these virtual field trips was a large undertaking, which is why Young hired a student to help. Rosa Toutah is currently completing a combined honours degree in Earth Sciences and Chemistry, entering her fourth year of study this fall. She started her co-op term in June and has been taking photos, filming, and editing. She goes out into the field with Young, gathers the data they need, then puts it all together in an interactive and accessible format.

She also works collaboratively with professors to ensure the theme is exactly what they’re looking for, while also offering her own student perspective on the quality and layout of the different learning materials.

These custom-made trips are from all across the province and showcase the beautiful landscapes of Nova Scotia, the majestic views of the Atlantic Ocean and the diversity of the east coast forests. These trips will allow students to learn about authentic landscapes and to explore the places that are important to their discipline of study. Both Young and Toutah feel confident that these virtual field trips will enable an enriching and immersive learning experience for all of their students — all from the comfort of their own home.

“In reality, you don’t need to love camping or hiking to be a great geologist or environmental scientist,” says Young. “This virtual field trip project was meant to be the beginning of a serious effort to cast a wider net, listen to our students needs during COVID-19, inspire both those that love and don’t love the outdoors, and reflect on the major positive aspects of this type of online learning.

“In fact, there are actually some things we just couldn’t do in-person that we can do with these virtual tools – I can’t wait to show these to our students.”

To learn more about the courses being offered this year by the Faculty of Science, visit the Dal Science hub and check out the course teasers.

Take a closer look at the virtual field trips by viewing some of the and gigapixel panoramas.

Mike Young would also like to recognize the incredible hard work of Jenn Strang in the GIS Centre as well as Max Lapierre in the Marine Affairs Program.